By: Boipelo Modise

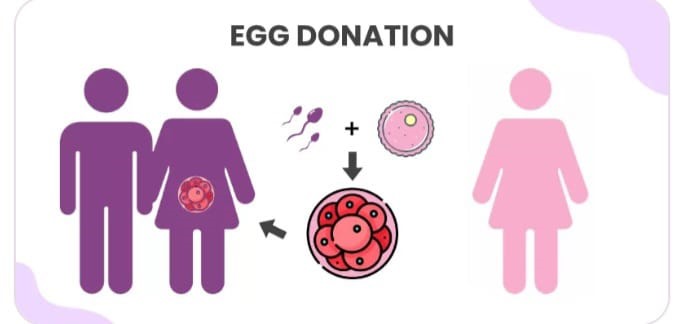

With youth unemployment at persistently high levels in South Africa, a growing number of young women are turning to egg donation as a way to generate much-needed income. Though the practice is legal and regulated, health professionals and ethicists warn of the potential risks and broader social implications.

For many, however, the urgent need for financial stability outweighs long-term health concerns. Donation is seen as a safer alternative to other informal income-generating activities.

“The National Health Act allows for reasonable reimbursement of expenses rather than direct payment for the donation itself. Regulations are continually reviewed to balance protecting donors from exploitation while respecting their autonomy. Future changes will be informed by ethical considerations, stakeholder consultation, and evidence-based research,” said Foster Mohale, Health Department spokesperson.

Under South African law, donors may be compensated for their time and effort, but not for the eggs themselves. Current guidelines cap reimbursement at about R8 000 per donation cycle. This amount reflects the significant commitment required: medical assessments, hormone injections, and multiple clinic visits. For young women struggling to survive in households below the poverty line, that sum can make a life-changing difference.

Egg donors undergo strict screening and remain anonymous, with laws limiting the number of children born from any single donor to six. While the ethical framework is in place, economic desperation drives many young women toward this option. Official studies have not directly linked egg donation to unemployment, but the connection is clear on the ground.

“I had no choice but to donate my eggs because I needed money. The procedure was painless and very quick. I got paid R8 000 for donating,” said Elizabeth, an egg donor.

Sperm donation, though less visible, also plays a role in South Africa’s reproductive health system. While compensation is lower than for egg donation, many young men see it as a way to earn supplementary income. Donors are rigorously screened, remain anonymous, and often describe the act as both financially helpful and a chance to support couples facing infertility.

The growing reliance on reproductive donation reflects South Africa’s wider socioeconomic crisis. High unemployment, limited job creation, and deepening poverty continue to push young people into unconventional avenues of income.

“My friend introduced me to the clinic because I needed money for school. The staff explained everything clearly, and I received R10 000 in Cape Town,” said Lindiwe, another egg donor.

Ultimately, egg and sperm donation in South Africa exist at the intersection of compassion and survival. For some, it is an act of generosity to strangers. For others, it is a financial lifeline in a country where too many young people remain locked out of the job market.